When it comes to building muscle, protein is often at the center of the conversation – and for good reason. This essential macronutrient plays a crucial role in muscle growth and repair. But beyond just how much protein you consume, a common question arises: How often should you eat protein to build muscle effectively?

Protein is fundamental to muscle development. It provides the amino acids necessary for muscle protein synthesis, the process by which your body creates new muscle tissue. Without adequate protein intake, your efforts in the gym may not translate to the muscle gains you’re aiming for.

However, the frequency of protein consumption can be just as important as the total amount. Many fitness enthusiasts wonder if they should concentrate their protein intake around workouts, spread it evenly throughout the day, or follow some other pattern for optimal results.

In this post, we’ll explore the science behind protein timing and frequency for muscle building. We’ll look at current research, practical considerations, and how you can apply this knowledge to your own nutrition strategy. Whether you’re new to strength training or a seasoned lifter, understanding these principles can help you optimize your approach to muscle growth.

Key Takeaways:

- Total daily protein intake is crucial for muscle growth and maintenance.

- Aim for 3-4 protein-rich meals (20-40g each) spread throughout the day.

- Research on optimal protein distribution is still evolving and sometimes inconsistent.

- Pre/post-workout and nighttime protein intake may offer additional benefits.

- Age, training status, and calorie intake influence protein utilization.

- Consistency in diet and exercise is more important than perfect timing.

The Role of Protein in Muscle Building

To understand why protein timing matters, we first need to grasp how protein contributes to muscle growth. At the heart of this process is muscle protein synthesis (MPS).

Muscle Protein Synthesis: The Building Process

Muscle protein synthesis is essentially your body’s way of creating new muscle tissue. Think of it as construction work at the cellular level. When you exercise, especially during resistance training, you create tiny tears in your muscle fibers. To repair and strengthen these fibers, your body initiates MPS.

During MPS, your cells use amino acids (the building blocks of protein) to repair damaged muscle fibers and create new ones. This process doesn’t just repair damage – it adapts your muscles to handle future stress by making them bigger and stronger. That’s how you gain muscle mass over time.

How Protein Intake Affects Muscle Growth

Your protein intake directly influences the rate and efficiency of muscle protein synthesis. Here’s how:

- Amino Acid Availability: When you consume protein, your body breaks it down into amino acids. Having a steady supply of amino acids in your bloodstream ensures your body has the raw materials it needs for MPS.

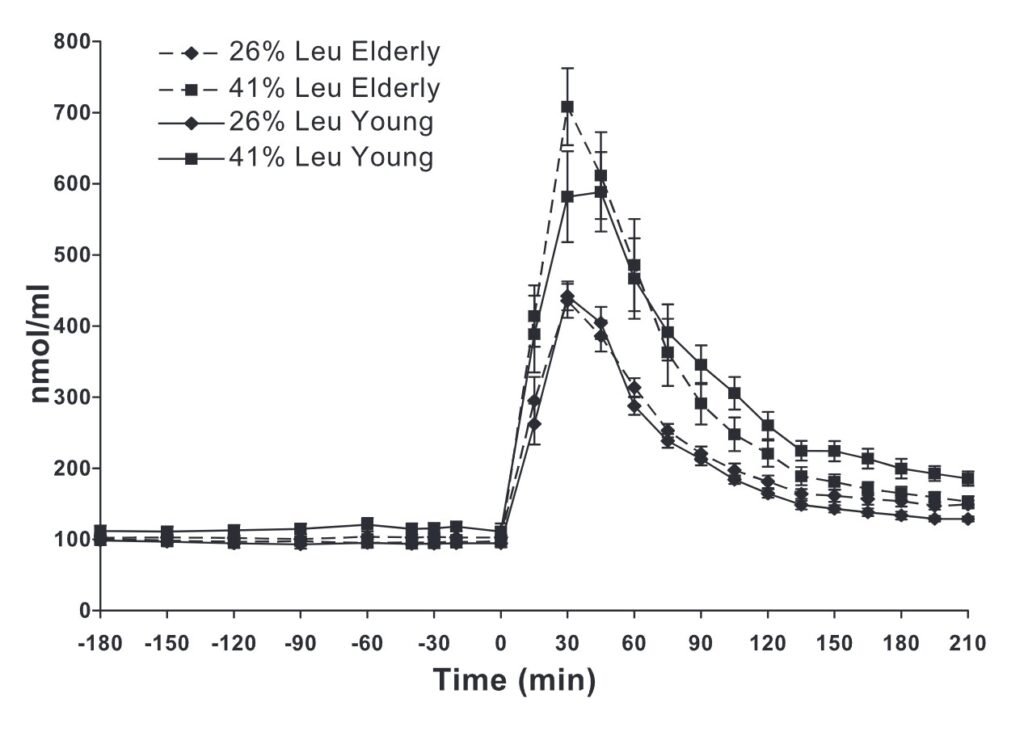

- Leucine Threshold: Of all amino acids, leucine plays a starring role. It acts as a trigger for MPS. Research suggests that reaching a certain threshold of leucine intake (about 2-3 grams) is crucial for maximally stimulating MPS.

- Balancing Synthesis and Breakdown: Your muscles are in a constant state of turnover, with protein synthesis and breakdown occurring simultaneously. Adequate protein intake tips this balance in favor of synthesis, leading to net muscle gain over time.

- Recovery and Adaptation: Protein doesn’t just fuel MPS – it’s essential for overall recovery. Proper protein intake helps reduce muscle soreness and improve performance in subsequent workouts.

- Hormonal Response: Protein intake can influence hormones that affect muscle growth, such as insulin and growth hormone.

It’s important to note that while protein is crucial, it’s not a magic bullet. Muscle growth is a complex process that also depends on factors like overall calorie intake, training stimulus, rest, and individual genetics. However, optimizing your protein intake – both in terms of quantity and timing – can significantly enhance your muscle-building efforts.

Daily Protein Requirements

When it comes to building muscle, protein intake plays a crucial role. But how much protein do we really need each day to support muscle growth? Let’s break it down:

Recommended protein intake for muscle building:

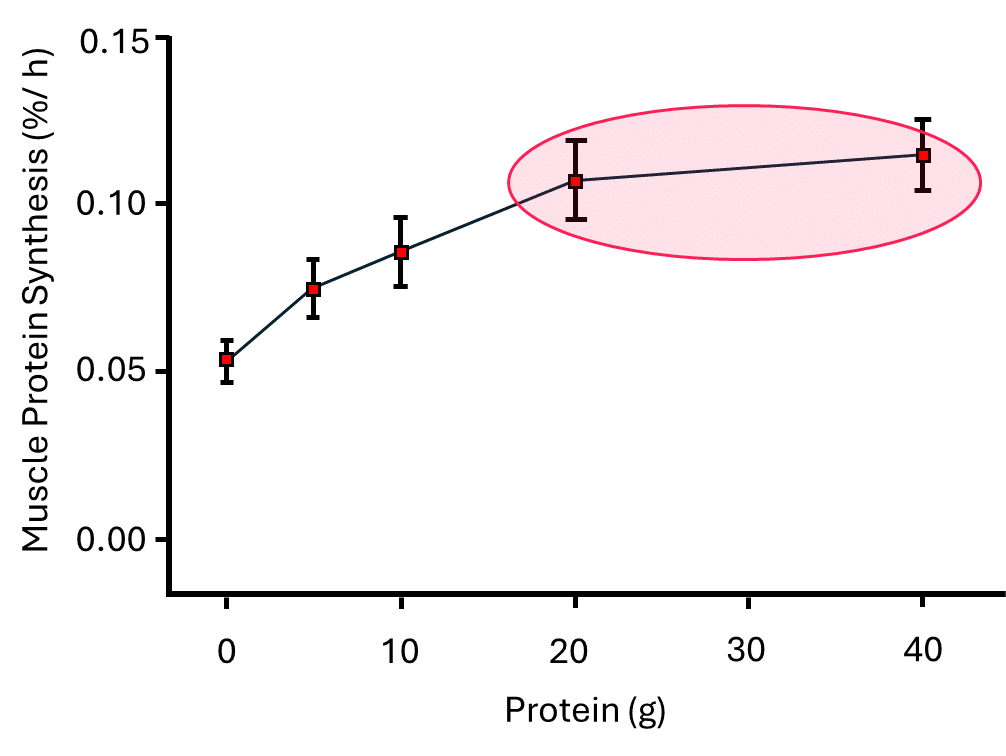

Research has shown that there’s a dose-response relationship between protein intake and muscle protein synthesis (MPS) – the process by which your body builds new muscle tissue. A landmark study by Moore et al. (2009) found that in young men, MPS increased with protein intake up to about 20-25 grams in a single meal. After this point, the additional protein didn’t further stimulate MPS, suggesting a saturation point.

However, this study was conducted on only six young males weighing approximately 85 kg. This raises the question, “What if these individuals were heavier?” Would MPS still be maximized at 20 g?

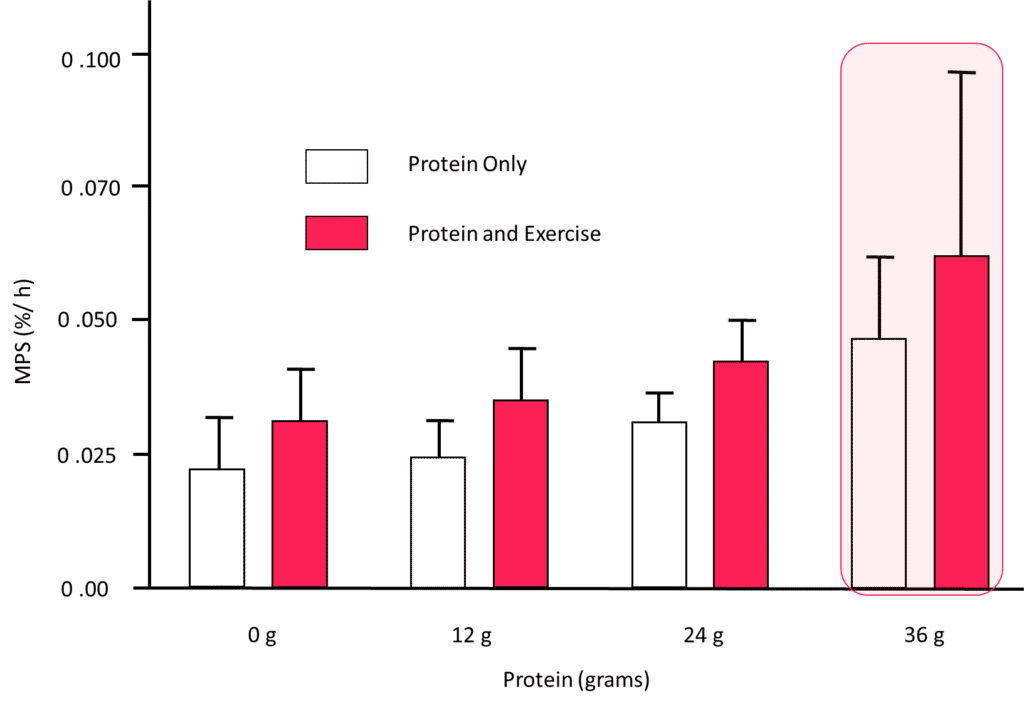

It’s important to note that this doesn’t mean you should limit yourself to 20-40 grams of protein per meal. More recent research, including a study by Robinson et al. (2012), has shown that older adults benefited from higher protein intakes. In this study, middle-aged men showed the greatest increase in MPS after consuming 170 grams of lean beef (providing 36 grams of protein), both at rest and after resistance exercise.

Factors affecting individual protein needs:

It’s crucial to understand that protein requirements aren’t one-size-fits-all. Several factors can influence how much protein an individual needs:

- Age: As we age, our muscles become less responsive to protein intake, a phenomenon known as “anabolic resistance.” This means older adults may need more protein to achieve the same muscle-building effect as younger individuals.

- Weight: Protein needs are often calculated based on body weight. The more you weigh, the more protein you typically need.

- Activity level: Athletes and those engaging in regular resistance training have higher protein requirements than sedentary individuals. Exercise increases protein turnover in the body, necessitating greater intake for recovery and growth, as seen in Moore et al. (2009) and Robinson et al. (2012).

- Training status: Beginners may see muscle growth with lower protein intakes, while more experienced lifters might need more to continue seeing gains.

It’s worth noting that our understanding of protein requirements has evolved over time. Initially, recommendations were based on nitrogen balance studies, which aimed to determine the minimum amount of protein needed to prevent deficiency. However, as pointed out by Robinson et al. (2012), these methods may underestimate the protein needs for optimal health and performance, especially in active individuals.

Current recommendations for strength athletes and bodybuilders often range from 1.6 to 2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. However, some research suggests that even higher intakes may be beneficial, especially when in a calorie deficit or for older individuals looking to preserve muscle mass.

Remember, while protein is crucial for muscle building, it’s just one piece of the puzzle. Adequate overall calorie intake, balanced nutrition, proper training, and sufficient rest are all essential components of a successful muscle-building program.

Protein Distribution Throughout the Day

The concept of protein timing:

Protein timing refers to strategically consuming protein throughout the day to maximize muscle protein synthesis (MPS). This concept has evolved from focusing solely on the post-workout “anabolic window” to a more comprehensive, day-long approach.

Spreading protein intake across the day is better for optimal muscle growth.

Research shows that MPS can be stimulated multiple times daily by consuming adequate protein. Each time you eat sufficient protein, you trigger a bout of MPS lasting about 3-5 hours. This understanding has led to the idea of spreading protein intake across the day for optimal muscle growth.

Optimal Frequency of Protein Intake

Research on protein feeding frequency:

The research on protein distribution and its effects on muscle mass is not yet completely clear. Hudson et al. (2020) point out in their review that the current evidence on the efficacy of consuming an “optimal” protein distribution to favorably influence skeletal muscle-related changes is limited and inconsistent. Many studies still look at the same number of feeding opportunities but with skewed distributions, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

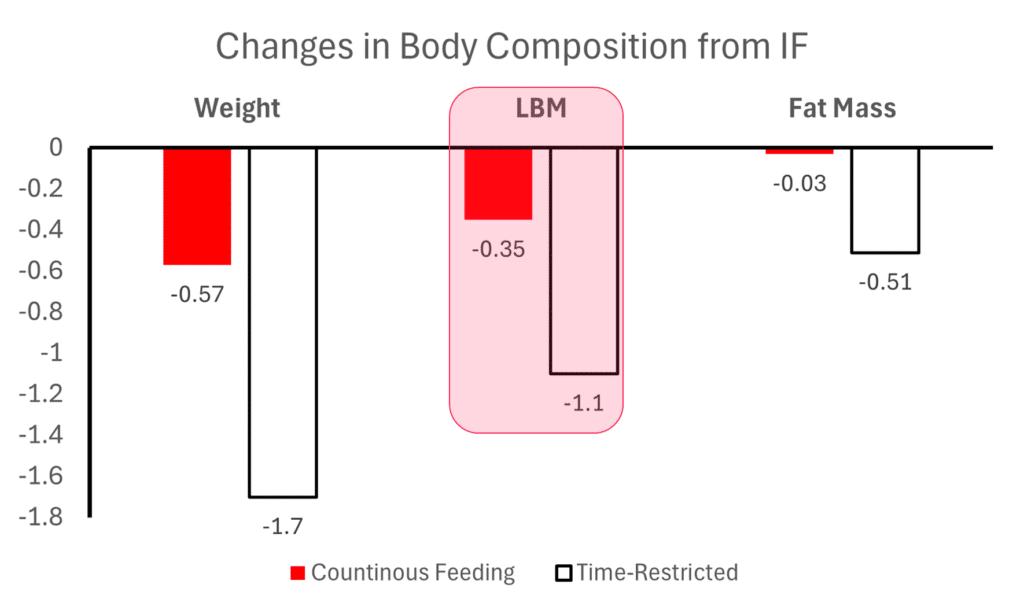

One area of interest that may provide some evidence is intermittent fasting. Some studies have found that intermittent fasting can lead to a loss of muscle tissue. For example, Lowe et al. (2020) conducted a randomized clinical trial examining the effects of time-restricted eating on weight loss and other metabolic parameters. They found that participants in the time-restricted eating group experienced a significant reduction in lean mass, with approximately 65% of the weight lost being lean mass. However, it’s important to note that the subjects in this study were untrained, and protein intake was not tracked, which limits the conclusions we can draw about protein distribution specifically.

On the other hand, Trabelsi et al. (2012) looked at recreational bodybuilders during Ramadan and found interesting results. In their study, individuals who fasted during Ramadan had no significant increases in lean body mass (-0.22 lbs), whereas the non-fasting group increased lean body mass by 1.54 lbs. While these results were not statistically significant, they suggest a potential trend. It’s worth noting that this study was only four weeks in duration, which may not have been long enough to detect significant changes in lean body mass.

These conflicting findings highlight the complexity of protein distribution and its effects on muscle mass. Factors such as training status, overall protein intake, and study duration can all influence outcomes, making it challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the optimal protein distribution for muscle growth and maintenance.

Nonetheless, with our understanding of protein kinetics and mechanisms, it would seem that eating protein more frequently would be more beneficial in gaining lean body mass.

The anabolic window: myth or reality?

The “anabolic window” refers to the purported short period after exercise when the body is especially primed for nutrient uptake and muscle growth. While this concept was once widely accepted, recent research has painted a more nuanced picture.

A comprehensive review by Aragon and Schoenfeld (2013) concluded that the anabolic window is much wider than previously thought. They found that total daily protein intake is more important for muscle growth than timing, especially in the context of a mixed meal eaten within a few hours before or after training.

However, this doesn’t mean timing is irrelevant. Consuming protein before and/or after training can still be beneficial, especially if you’re highly trained ( see Cribb et al. 2006), or it’s been several hours since your last meal. The key is to ensure you’re meeting your total daily protein needs and consuming protein at regular intervals throughout the day.

In practice, aiming for 3-5 protein-rich meals spread evenly throughout the day, with one of these meals falling within a few hours before or after your workout, is likely to cover all bases for optimizing muscle protein synthesis and growth.

Remember, while these strategies can help optimize results, they’re not more important than consistency in overall protein intake, calorie balance, and progressive resistance training. These fundamental principles remain the cornerstone of effective muscle building.

If you are a highly trained resistance trained individual, there is evidence to support that timing may still be important.

Practical Recommendations

While research on optimal protein distribution is ongoing, there are some practical recommendations we can make based on current evidence:

Suggested meal/snack timings for optimal protein intake:

- Aim for 3-4 evenly spaced protein-rich meals throughout the day

- Include a protein source with breakfast, lunch, and dinner

- Consider a pre-sleep protein snack, especially on training days

Examples of protein-rich (high leucine content) foods and their portion sizes:

- Chicken breast (3 oz): 26g protein

- Greek yogurt (6 oz): 17g protein

- Eggs (2 large): 12g protein

- Salmon (3 oz): 22g protein

- Lean beef (3 oz): 22g protein

- Tofu (1/2 cup): 10g protein

- Whey protein powder (1 scoop): 20-25g protein

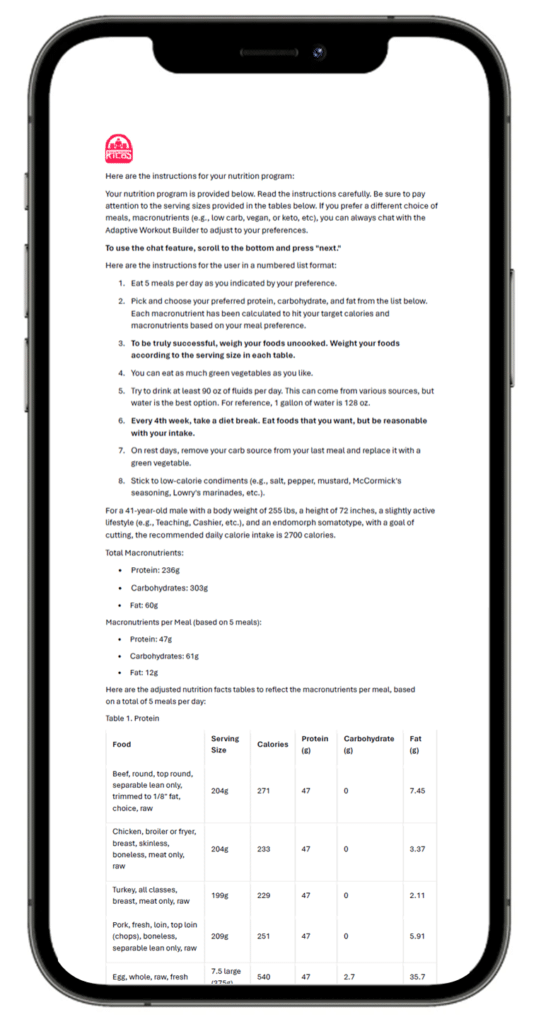

Body Composition Calculator

Transform Your Nutrition with Our Body Recomp Calculator

- Personalized Meal Plans: Tailored to your fitness goals and dietary preferences.

- Flexible Options: Choose from various meal types to fit your schedule.

- Nutritional Guidance: Expert advice to optimize your performance and recovery.

- Progress Tracking: Monitor your nutrition intake and make adjustments easily.

- Easy Recipes: Simple, delicious, and healthy meals to keep you on track.

To help determine your specific protein needs based on your goals, body composition, and activity level, try out our body recomposition calculator. This tool can provide personalized recommendations for your entire diet.

Special Considerations

Pre and post-workout protein intake: Consuming protein before and after workouts can help support muscle protein synthesis. Aim for:

- Pre-workout: 20-30g protein about 1-2 hours before exercise

- Post-workout: 20-40g protein within 2 hours after exercise

Including creatine monohydrate: Creatine can enhance the effects of resistance training on muscle mass and strength. Consider adding 3-5g of creatine monohydrate daily, preferably post-workout or with a meal containing carbohydrates.

Nighttime protein consumption: Some research suggests that consuming 30-40g of a slow-digesting protein (like casein) before bed may help support muscle protein synthesis during sleep. This can be particularly beneficial for those looking to maximize muscle growth or prevent muscle loss during calorie restriction.

Remember, while timing and distribution of protein intake can be optimized, the most crucial factor is meeting your total daily protein requirements. Consistency in your overall protein intake, combined with a well-designed resistance training program, will be the primary drivers of muscle growth and maintenance.

Conclusion

The concept of protein distribution throughout the day and its impact on muscle growth and maintenance is an area of ongoing research. While the evidence is not yet conclusive, several key points have emerged from our discussion:

- Total daily protein intake remains the most crucial factor for muscle growth and maintenance.

- Spreading protein intake across 3-4 meals throughout the day may offer benefits for muscle protein synthesis, especially in older adults or those looking to maximize muscle growth.

- Consuming 20-40g of high-quality protein per meal appears to be a good target for most individuals.

- Pre and post-workout protein intake, as well as nighttime protein consumption, may provide additional benefits for muscle growth and recovery.

- Factors such as age, training status, and overall calorie intake can influence the body’s response to protein intake and distribution.

It’s important to emphasize that while optimizing protein distribution can be beneficial, consistency in both diet and exercise is paramount. Remember, small optimizations in protein timing and distribution should be viewed as fine-tuning rather than the foundation of your nutrition strategy. Focus on establishing sustainable habits that allow you to consistently meet your protein needs and adhere to your exercise routine.

References

Atherton, P. J., & Smith, K. (2012). Muscle protein synthesis in response to nutrition and exercise. The Journal of Physiology, 590(Pt 5), 1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225003

Cribb, P. J., & Hayes, A. (2006). Effects of supplement timing and resistance exercise on skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 38(11), 1918–1925. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000233790.08788.3e

Hudson, J. L., Iii, R. E. B., & Campbell, W. W. (2020). Protein Distribution and Muscle-Related Outcomes: Does the Evidence Support the Concept? Nutrients, 12(5), 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051441

Jäger, R., Kerksick, C. M., Campbell, B. I., Cribb, P. J., Wells, S. D., Skwiat, T. M., Purpura, M., Ziegenfuss, T. N., Ferrando, A. A., Arent, S. M., Smith-Ryan, A. E., Stout, J. R., Arciero, P. J., Ormsbee, M. J., Taylor, L. W., Wilborn, C. D., Kalman, D. S., Kreider, R. B., Willoughby, D. S., … Antonio, J. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Protein and exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-017-0177-8

Katsanos, C. S., Kobayashi, H., Sheffield-Moore, M., Aarsland, A., & Wolfe, R. R. (2006). A high proportion of leucine is required for optimal stimulation of the rate of muscle protein synthesis by essential amino acids in the elderly. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 291(2), E381-387. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00488.2005

Kim, J. (2020). Pre-sleep casein protein ingestion: New paradigm in post-exercise recovery nutrition. Physical Activity and Nutrition, 24(2), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.20463/pan.2020.0009

Lowe, D. A., Wu, N., Rohdin-Bibby, L., Moore, A. H., Kelly, N., Liu, Y. E., Philip, E., Vittinghoff, E., Heymsfield, S. B., Olgin, J. E., Shepherd, J. A., & Weiss, E. J. (2020). Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Women and Men With Overweight and Obesity: The TREAT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(11), 1491–1499. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4153

Moore, D. R., Robinson, M. J., Fry, J. L., Tang, J. E., Glover, E. I., Wilkinson, S. B., Prior, T., Tarnopolsky, M. A., & Phillips, S. M. (2009). Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(1), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2008.26401

Ratamess, N. A., Kraemer, W. J., Volek, J. S., Rubin, M. R., Gómez, A. L., French, D. N., Sharman, M. J., McGuigan, M. M., Scheett, T., Häkkinen, K., Newton, R. U., & Dioguardi, F. (2003). The effects of amino acid supplementation on muscular performance during resistance training overreaching. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 17(2), 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2012-0092

Schoenfeld, B. J., Aragon, A. A., & Krieger, J. W. (2013). The effect of protein timing on muscle strength and hypertrophy: A meta-analysis. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 10(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-10-53

Tinsley, G. M., Forsse, J. S., Butler, N. K., Paoli, A., Bane, A. A., La Bounty, P. M., Morgan, G. B., & Grandjean, P. W. (2017). Time-restricted feeding in young men performing resistance training: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(2), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2016.1223173

Trabelsi, K., Stannard, S. R., Maughan, R. J., Jammoussi, K., Zeghal, K., & Hakim, A. (2012a). Effect of resistance training during Ramadan on body composition and markers of renal function, metabolism, inflammation, and immunity in recreational bodybuilders. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 22(4), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.22.4.267

Trabelsi, K., Stannard, S. R., Maughan, R. J., Jammoussi, K., Zeghal, K., & Hakim, A. (2012b). Effect of resistance training during Ramadan on body composition and markers of renal function, metabolism, inflammation, and immunity in recreational bodybuilders. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 22(4), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.22.4.267

Zaromskyte, G., Prokopidis, K., Ioannidis, T., Tipton, K. D., & Witard, O. C. (2021). Evaluating the Leucine Trigger Hypothesis to Explain the Post-prandial Regulation of Muscle Protein Synthesis in Young and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8, 685165. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.685165

Ive read several just right stuff here Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting I wonder how a lot effort you place to create this kind of great informative website

Pingback: Choosing the Best Proteins for Muscle Growth